Comments – University of British Columbia, Affiliated Research Ethics Board

Notice

Comments are posted in the language in which they were received.

Dear Secretariat,

Please find attached our comments on the proposed revised guidance on Ethics Review of Multijurisdictional Research for your consideration. These are being made on behalf of the University of British Columbia’s Affiliated REBs, with the specific exception of the BC Cancer REB, and on behalf of Research Ethics BC. As noted in the attachment, the comments have been compiled by:

- Sarah Bennett, Manager, Research Ethics and Compliance, Island Health

- Laurel Evans, Director Research Ethics, University of British Columbia

- Terri Fleming, Director of Research Ethics BC

- Julie Hadden, Manager, Research Ethics, Providence Health Care

- Eugenie Lam, Manager, Research Ethics, University of Victoria

- Sara O’Shaughnessy, Manager, Research Ethics and Compliance, Fraser Health

- Jean Ruiz, Senior Research Ethics Analyst – Behavioural Office of Research Ethics, UBC and Senior Advisor and Solutions Liaison to Research Ethics BC

In addition, our response has received specific endorsement from the following individuals:

- Dr. Davina Banner-Lukaris, Chair of Research Ethics Board, University of Northern British Columbia

- Dorothy Herbert, Research Ethics Board Coordinator, Interior Health

- Heather Fudge, Chair of Research Ethics Board, Island Health

- Karin Maiwald, Member of Research Ethics BC Advisory Council, and Adjunct Faculty, UBC

- Chris Turner, Research Ethics Officer, Vancouver Island University

We look forward to your response.

Kindest regards,

Terri Fleming, MBA

Unit Director

Comments from Research Ethics BC and UBC Panel on Research Ethics Proposed Revised Guidance

Dear Secretariat: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the proposed revised guidances for the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2018(2). The current response is limited to the proposed revised guidance on Ethics Review of Multijurisdictional Research.

These comments are being made on behalf of the UBC Affiliated REBs, with the specific exception of the BC Cancer REB, and on behalf of Research Ethics BC (REBC). REBC supports the province-wide harmonized system for research ethics reviews of studies conducted in multiple geographic areas involving the resources, people, patients or data from more than one BC Research institution. The REBC network currently has 22 active Research Ethics Boards (REBs) across colleges, universities, and health authorities. Between them, there are 400 research sites. UBC has six affiliated REB’s which have been operating under a one REB of record agreement since 2006.

These comments have received review and input from the following members of the REBC Advisory Council and Secretariat:

- Sarah Bennett, Manager, Research Ethics and Compliance, Island Health

- Laurel Evans, Director Research Ethics, University of British Columbia

- Terri Fleming, Director of Research Ethics BC

- Julie Hadden, Manager, Research Ethics, Providence Health Care

- Eugenie Lam, Manager, Research Ethics, University of Victoria

- Sara O’Shaughnessy, Manager, Research Ethics and Compliance, Fraser Health

- Jean Ruiz, Senior Research Ethics Analyst – Behavioural Office of Research Ethics, UBC and Senior Advisor and Solutions Liaison to REBC

These comments represent commentary from biomedical, behavioural sciences, health sciences, humanties , and other research disciplines. We have included a series of general comments concerning the purpose and objectives of the proposed revised guidance followed by specific comments directed to the Guidance Content, Scope and Proposed Process.

General Comments

We wholeheartedly support the objective of developing new guidance encouraging a departure from the model of multiple single-site reviews of multi-jurisdictional studies and moving toward a model encouraging the minimum number of necessary ethics reviews combined with a goal to achieve maximum reciprocity (direct acceptance) of reviews performed by other qualified REBs.

BC has utilized a model of harmonized reviews for multi-jurisdictional studies since 2016. Since 2018 the Provincial Research Ethics Platform (PREP) has been housed in the UBC RISe system and shares a common multi-site application form. It is not restricted to minimal risk or to behavourial research.

1. Review by a single REB is not the same as a single ethical review.

While we support the overall objective of the proposed revised guidance, we believe that there has been inadequate examination of the consequences of making review by a single REB mandatory for all minimal risk research that is conducted under the auspices of multiple institutions, particularly in the health authority context. Proposing a single model for multi-site review without giving consideration to the various models that have been attempted and been adopted by different provinces and institutions is dismissive of those successful models, We wish to emphasize that review by a single REB is not the same as a single ethical review. BC’s model successfully implements the latter while specifically avoiding requiring the former. Our primary point in this response is that we are strongly opposed to the imposition of a model of review by a single REB. Mandating such a model would effectively require dismantling of the entire BC harmonization system at great cost, with no benefits.

2. Detail and flexibility

Our second major concern with the proposed guidance is that it needs to offer the necessary degree of detail and flexibility that is required for a cooperative review model. On the surface, mandating a single ethical review by a single REB appears to be relatively simple to implement. Any models implemented must however, consider the REBs monitoring and post-approval responsibilities. They must also accommodate circumstances where institutions have online systems, as well as when they are integrated with other institutional processes including funding and conflict of interest. The capacity to accommodate local institutional approvals is crucial for research in health authorities. The proposed Guidance notes that the examples of harmonized review referenced “are the result of formal agreements which took time to negotiate”. [Lines 49-50]. The BC experience has been that the formal agreements have been the least problematical piece required in adopting harmonized reviews. The most challenging and time consuming part of implementing harmonized review has been developing the model to be used for the review so that it meets the needs of all involved parties. While the guidance does state that a single ethical review should be mandatory, it also provides for lee-way in cases where “local circumstances merit additional scrutiny”. [Lines 45-46] Those circumstances are not well defined in the guidance, and while the guidance states that “Review by a single REB affords a second opportunity for consideration of the ethical impact of the research on all participants at all sites” [Lines 66 – 67] it is not clear how this is intended to be accomplished. The proposed guidance does not adequately consider the respective roles and responsibilities of the Reviewing REB’s institution or the delegating REB’s institution. It leaves a number of crucial communication requirements “up to the researchers” which in our collective opinion, is a very unrealistic expectation. The BC experience has shown that very clear and specific models/standard operating procedures (SOPs) and a connected trusting REB community are keys to success in implementing harmonized reviews.

Imposing mandatory single review by one REB without clear models and processes for the entire life-cycle of a study will cause confusion for researchers who will face inconsistent processes across sites. It will overburden REB staff with the need to consult on each individual project for reporting purposes and to track down all studies that may be happening in their institutions and/or involving their investigators. It is our preference that PRE consider developing overarching high-level principles that apply to multijurisdictional review. This could include a mandate requiring REBs and their institutions to streamline ethical review and oversight processes. Any principles adopted must give REBS and their institutions within and across regions of Canada, the flexibility to interpret and apply the overarching principles to best meet regional, provincial and national needs and requirements. This would allow regions to work within their already functioning partnerships to fine tune and extend their models. For example, the BC model allows for REBs to grant direct reciprocity to another Board, meaning that participating partner boards can defer to the Board of Record for review and approval. This accomplishes what PRE is recommending but also allows for some flexibility and upfront consideration of local circumstances.

3. Requirements of research involving Indigenous peoples and communities

Critically, the proposed guidance does not take into account the unique circumstances that apply to research involving Indigenous people, where for example, one minimal risk study may have multiple researchers engaging with multiple Indigenous communities. Each has unique local considerations that must be accounted for and for which it would be difficult for a single REB to adequately take into account in the approval process, and more particularly in the course of monitoring the study. As is articulated in TCPS 2018 (2), Chapter 9, research involving Indigenous peoples is premised upon respectful [personal] relationships and is very much tied to the land and/or place where it is proposed to be occurring. The proposed model is not congruent with the requirements of Chapter 9 regarding previous approvals and engagement with communities. It dismisses the sovereign rights of Indigenous peoples, communities and Nations, and does not allow for relationships to be developed.

4. The American Model

It is true that in the United States, the regulation regarding cooperative research applies to all federally funded research. The funding agency or department is given the authority to determine that the use of a single IRB is not appropriate in a particular context [45CFR46.114(b)(2)(ii)]. Research involving American Indian or Alaskan Native tribes is specifically excluded [45CFR46.114(b)(2)(i)] Unfunded research which constitutes a large proportion of minimal risk level research is not subject to the requirement, and in fact much of the minimal risk research that is required to be reviewed in Canada is exempt from review in the United States. The regulation only applies to funded research that involves more than one institution and which warrant contractual arrangements for many reasons. Reliance agreements articulating the roles and responsibilities of both the reviewing IRB and Institution, as well as the relying IRB and Institution are a standard requirement and considered part of the funding agreement process. In effect, the model is a delegated review model, but there are formally agreed upon roles and responsibilities, including those covering consideration of local circumstances, reporting obligations, informing the non-reviewing institutions of post approval activities, etc. In effect, specifics of the review model and how they apply to each institution are articulated in the reliance agreement.

Comments on the Guidance

We completely endorse the articulated policy basis for a single review of multi-jurisdictional research. We agree that all researchers must apply a common set of ethical principles to the design and conduct of their research, and that all REBs must review research based on those same common ethics principles and guidance.

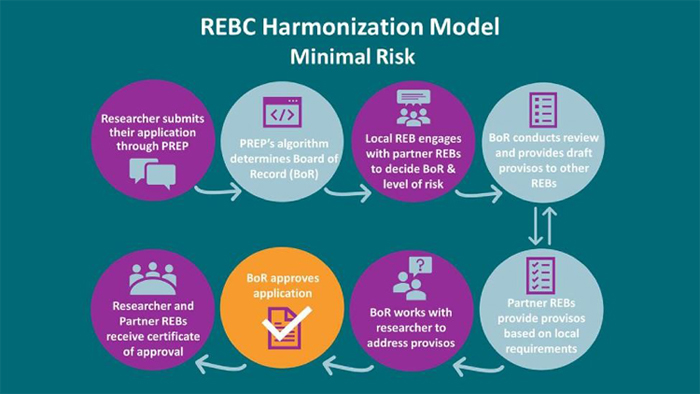

We agree that a single review of minimal risk research should not compromise participant protection. We are unsure how review by a single REB “affords a second opportunity for consideration of the ethical impact of the research on all participants at all sites”. The practical reality is that often not all sites where the research is going to take place are known to the research team when the initial REB review takes place. Many sites are added on in subsequent amendments. A single comprehensive review is a laudable objective, but it cannot be easily accomodated if the review is by a single REB. BC’s model of collaborative or harmonized review (see Figure 1) provides an opportunity for: a) a single comprehensive review involving voluntary input from each impacted REB; b) the opportunity for an REB to determine that it is not necessary for them to provide input at the initial review; c) a process that allows for the input of additional sites to be given consideration even after initial approval; d) shared accountability by way of a multi-site, multi-institutional research ethics approval (not an “acknowledgment”) and; e) voluntary input into post-approval activities that impact any site. In addition, the collaborative single review model allows for a REB of Record chosen by way of a pre¬determined algorithim (with flexibility for change upon agreement of the participating REBs) to be the REB which maintains primary oversight and monitoring of the study.

By contrast, the proposed model is a delegated review model, which does not allow for voluntary input from an impacted REB and its institution in the course of the initial review. It presumes that in most instances, it is not necessary for the other REBs to provide input and it assumes that the research team will be aware of and make the reviewing REB aware of all local considerations at all contemplated sites. Regrettably, this is virtually never the case. The proposed model does not allow for shared accountability by way of a multi-institutional ethics approval. It suggests that local considerations can be communicated to the Reviewing REB, subsequent to initial approval based upon an acknowledgment process undertaken by a local administrator. This could potentially require multiple amendments to the initial approval as each site undergoes the acknowledgment process. It also leaves the responsibility for providing the REB of Record documentation to the local REB and Institution up to the researchers. This is not a realistic expectation.

Comments on Scope

1. Minimal risk

As you are aware, the TCPS(2) 2018 does define research that it considers to be qualified for minimal risk review as follows: “For the purposes of this Policy, “minimal risk” research is defined as research in which the probability and magnitude of possible harms implied by participation in the research are no greater than those encountered by participants in those aspects of their everyday life that relate to the research.” We are concerned that REBs will not always agree upon the application of this definition. What if one REB believes the study is minimal risk whereas another views it as higher risk? This is particularly important given that context is always key. What is minimal risk in one place may not be in another. Similarly, there is no consideration of how to deal with studies that start out as minimal risk, but then by amendment, increased risks are added so that the study requires full REB consideration.

Given our responses pertaining to the proposed revised guidance in relation to minimal risk studies, we do not feel that it is necessary at this point, to review all of the challenges related to imposing a single REB review on above minimal risk research, particularly that which is unfunded and/or privately sponsored. We will limit our comments to addressing the suggestion that: “In the case of research involving more than minimal risk, however, there is a greater likelihood that a missed issue could have a substantive impact on participant welfare. For this reason, there should be an opportunity for local review.” [Lines 154 – 156]. In addition to the complexities of applying a single REB model in research that involves more than minimal risk, it would appear, at least on the face of it, that this suggestion specifically recommends a secondary review in such instances. The distinction between this recommendation and a “review for acknowledgment” in the minimal risk context is unclear.

2. Academic Institutons vs. Health Authorities

The proposed revised guidance does not distinguish between minimal risk studies that are primarily behavioural and taking place at academic institutions, and those that are primarily clinical and taking place within a hospital or health authority. The proposed guidance seems to have been drafted utilizing a model of multi-site survey research at different academic institutions. The scope of minimal risk research is much broader than that portrayed in the model.

The concerns of clinical sites differ substantially from those of academic sites, including:

- Requirement for local involvement: Minimal risk research would rarely be conducted by the same researcher at multiple clinical sites/institutions. In general, research conducted within a health authority or a hospital would be conducted by someone with an affiliation with the institution. Researchers need to be familiar with hospital/health authority processes including patient and patient record access requirements. As minimal risk research in the clinical setting could involve review of patient records, procedures such as blood draws, medical imaging, or other types of minimal interventions, this type of minimal risk study does not lend itself to being reviewed by an REB external to the institution. The local REB for that institution needs to be aware of the credentials of the investigator, and the responsibility of the local institution for protection of patient privacy. If a clinical site were to “acknowledge” an ethical review by an external REB, there would need to be a mechanism in place to ensure that the external REB would notify the local site REB of situations involving protocol deviations or non-compliance by the local researcher(s). In such instances, the local site must have input into the appropriate mitigation measures and a way of ensuring that the local researcher would agree to be subject to the overseeing Board’s authority.

- Requirement for institutional resource approval: While theoretically multiple clinical sites could “accept” an REB review by an external REB, there would have to be some mechanism in place for the research to receive institutional (hospital / health authority approval). In the current environment, many hospitals and health authorities rely upon their REB office to be the starting place to initiate these approvals. Ignoring the reality that most clinical institutional approval and finance processes have been developed on the back of the local REB review is a significant problem for the proposed guidance. Most hospital sites will not provide services (laboratory, pharmacy, etc.) without local REB approval. Not recognizing and attempting to integrate this into the proposed process will create significant confusion and work for local REB staff and for hospital service providers.

- Legislative requirements: Many provinces require or even legislate review and approval of health related research. In most of these instances, the review must be by a specifically delegated and qualified REB which has reporting obligations to the Provincial Privacy Commissioner. for example, the Alberta Health Information Designation Regulation, Regulation 69/2001]

3. Funded vs. Unfunded Research

If the guidance applied only to multi-provincial funded research, there could be a way through the funding agreement to articulate the roles and responsibilities of each institution, including whose REB would review and oversee the study. This would be similar to the US model. The funding agencies would have to allow for this kind of delegation to another REB and the offices overseeing release of grant funding would have to be aware of the delegation. If the guidance applies to funded and unfunded research (the latter of which constitutes the vast majority of social sciences behavioral minimal risk research) then in general there would be numerous studies that would either have to develop an agreement or which would not have one [Line 146]. As previously pointed out, a written standard operating procedure outlining in detail the process to be followed for a harmonized or delegated review is absolutely fundamental to retaining efficiency of harmonized reviews. While that may not have to be a “formal agreement” at the highest level of the institution, it fundamentally must detail roles and responsibilities, and it is unrealistic to leave those “up to the researcher or researchers”. At UBC, the Human Research Policy (LR9) allows for delegation of review authority to another REB, however, it requires that the Institution take into account the manner in which the other Institution’s REB conducts its reviews, and it requires that the Chairs of the UBC affiliated REBs be consulted.

4. Meaning of the term acknowledgment

The proposed Guidance introduces the concept of an “REB acknowledgment” of another REB’s review and approval. The meaning of this term and the implications of acknowledgment are unclear. Does the term mean acceptance of the review and adoption of the approval such that the institution is deemed to have delegated the review to another institution? Is there an actual approval by the local site? Does it simply indicate that the local institution is aware that the study has been reviewed and approved and that in some way (either by researcher or resource involvement) it is impacted by the study? Where there is an acknowledgment, and the Board of Record has issued the approval and is responsible for post-approval activities, does this mean that the Board of Record is responsible for researcher compliance?

The US regulations require that an IRB shall review and “have authority to approve, require modifications in(to secure approval) or disapprove all research activities covered by this policy” [42CFR46.109a] Each institution that receives US Federal funding and that is engaged in research covered by the US policy needs to provide written assurance that it will comply with the Policy requirements. [42CFR46.103a] Will US funded research be excluded from the scope of the Guidance? Or does local site acknowledgment of an REB approval by a Board of Record also constitute authority to approve, require modifications, or disapprove US funded research on its behalf? If so, the Board of Record needs to be listed under the local site’s Federal Wide Assurance (FWA) as an authorized REB.

5. Responsibility

-

The Choice of the Board of Record: The choice of the REB with the “authority to conduct the review” and that has the “responsibility for continuing ethics review”, i.e. the Board of Record, assumes that there is a lead principal investigator, when for many multi-site minimal risk studies this is not the case. [Lines 98-99]. The guidance proposes that the decision to have another REB appointed as the Board of Record is to be determined by the lead PI’s REB, after justification of the change is made to it by the Researcher.

It is also inappropriate for a “lead principal investigator” to be making the determination that another Board would be more appropriate to be the Board of Record. This should be a determination made by and agreed upon by the potentially involved REBs. In the BC model of harmonized review, the algorithm agreed by the partners to the model determines the Board of Record based on where the majority of the research will take place –the affiliation of the principal investigator, and the location of the participants. In other words, which institution has the most involvement in the conduct of the study, and knowingly accepts this responsibility based on the information provided by the researcher/PI . This model also allows for the REB Administrators to assign the Board of Record based on other agreed characteristics, such as expertise of a specific REB.

Taking into consideration local circumstances, not just in the initial review but also in continuing review: The process proposed for taking into consideration local circumstances is unclear. It has been the BC experience that most multi-jurisdictional studies do have “local circumstances” that need to be considered. In addition to the circumstances cited in the proposed revised guidance, local circumstances are frequently about:

- how recruitment will take place at an institution;

- rules respecting data storage and retention;

- the transfer of human samples from a university or health clinic to another university’s labs for specialized analysis (and possible re-use by researchers at the second university going forward); or

- whether health data will transmitted/shared from a hospital to a university’s analyst team outside of the hospital; or

- Catholic institutions that have their own unique requirements.

If the local REB only receives the notification that its institution is somehow involved in a study after an approval by a Board of Record, what assurance does it have that local circumstances have been addressed? If the local REB does choose to ask the REB of Record to “reconsider” its decision, and an approval has already been issued, what does this mean operationally? Is the approval suspended or retracted? If so for all sites or for some? What if the REB of Record decides that local circumstances are not significant enough to warrant a revision of the approval decision? Does this process occur consecutively or concurrently amongst local REBs? How does the REB of Record track these changes and notify the local REBs?

- Leaving responsibility to researchers: The proposed revised Guidance states that “both the researcher (research team) and the REB of record should have considered local circumstances (i.e. circumstances unique to the particular site, such as specific participant demographic, language, culture not necessarily present at other sites as part of the study design and the review respectively”. [Lines 86¬90] As we have already pointed out, regrettably, it has been our experience that non-local sites are not always aware of the unique challenges facing other sites. Researchers may not consider these issues from a participant perspective, and may not communicate with each other when they design a study, receive funding or discuss the research ethics submission(s). As well, it is not always apparent at the time of the initial review which sites will become involved. The Guidance states that: “The intention is to keep the REB of record as the sole REB that can make changes to the terms of the ethics approval.” [Lines 91 -93]. However, without a formalized structure and required timelines for receiving and responding to such input both at the time of the initial approval and when major changes to the research occur, there can be no assurance to the non-reviewing institution that its concerns will be considered or that it will be notified.

- Leaving responsibility for “providing” local REBs with all documentation along with evidence of the ethics approval from the REB of record and the final version of the study as approved by that REB is setting up the potential for local REBs (and their institutions) not being notified. This potentially exposes instiutions to non-compliance which institutions will be expected to address and resolve. Similarly, giving researchers the responsibility for sending the local acknowledgment to the Board of Record is setting up the potential for lack of notification of the Board of Record. Finally, giving researchers the responsibility for notifyiing the local site of any further “decisions” by the REB of Record is allocating to them a responsibility that could be highly onerous and time consuming, let alone confusing in so far as tracking is concerned. Additionally this proposed process would not seem to allow for local REB involvement in post-approval activities, many of which may be directly related to them. For example site specific adverse events or unanticipated problems, closures at one site before others, changes of Investigators at local sites etc.

Comments On Process

1. Documentation / Applications

The assumption appears to be that the documentation will be that of the Board of Record, i.e. their application form. This does not account for differences between applications, including clinical vs. behavioral research, differing or non-existent Indigenous involvement questions, or Institution specific requirements.

2. Online Systems

For institutions that have online systems that are generally tied to funding release, auditing, conflict of interest compliance, and links to human resources and financial systems, “provision” of “all documentation” is potentially problematical. Either the local researcher will have to complete the local REBs application form, or an offline system for maintaining records and tracking of “acknowledged” studies will have to be developed. Currently no institutional online systems that we are aware of have processes set up for allowing external REB approvals to “get into” their system. The process of “receiving external documentation” by an online system could entail major platform revisions and expense.

3. Post Approval Activities

The proposed revised model and the Guidance refer to continuing ethics review in one sentence at Lines 98 and 99. “The REB of record has the responsibility for continuing ethics review.” With respect, the guidance assumes that initial REB approval is the most significant part of the research ethics review process. In reality, continuing review and oversight and monitoring of the conduct of a study comprise the majority of the process of ethical review. Even for simple minimal risk behavioural academically centred research, multiple amendments are common. The breadth of this kind of activity ranges from simple changes in personnel, to required revisions to the informed consent, and includes study closures, which could be at different times at different sites. Any model being proposed for harmonized or “single” ethical review must provide detailed guidance pertaining to how post approval activities will be handled, and in particular timing of and processes for notification of impacted REBs. In particular, the Guidance needs to address how the local REB is informed/assured of site compliance with approved study documents, and that unanticipated problems are addresssed, particularly in cases where problems are systematic and/or repetitive. With regard to study closures, there are a range of issues that arise when research teams do not communicate effectively between sites, including dispursement of funds to expired studies, and ethics file closure because one site has completed their activities while the rest of the sites are still running. This is a significant deficiency in the Guidance that needs to be addressed.

4. Requirement for agreements and detailed standard operating procedures

The current models that have been developed for harmonized review across Canada are significantly more detailed with respect to obligations, reporting requirements and required agreements and processes, including detailed written standard operating procedures. The single IRB review requirement for funded research taking place in the US, is a clearly delineated delegation of review and monitoring responsibility, accompanied by a formal legal agreement. If the intention is to set up a system of mandatory delegated reviews for minimal risk research, the articulation of the responsibilities of each of the parties involved in the delegation process, need to be clearly described in a written agreement. This is the model that has been adopted by the Ontario Cancer Research Ethics Board, and Clinical Trials Ontario. In our respectful submission, it would be a mistake to impose this model upon minimal risk unfunded research because of the potential need for multiple formal agreements related to unfunded research.

Suggested Next Steps

From BC’s perspective, we cannot emphasize the potential negative impact to BC’s already developed system of harmonized review too greatly. The scope of the impact will be borne by BC researchers (faculty and graduate students), academic institutions and health authorities alike, and will place additional burdens on our institutions, many of whom continue to struggle with understaffed REB and research administration offices.

We urge the Panel to reconsider the proposed “review by a single REB model” and at the very least to allow for different models and workflow processes for streamlining depending upon the research context and the configuration of the given study including the factors listed under Scope. If a single REB review model is recommended, we ask that the concept encompass “a single REB review” including but not necessarily requiring “review by a single REB”.

We suggest that an environmental scan, examining the current harmonization / streamlining processes of each Canadian province be conducted. We suggest that there be a formal consultation process asking REB administrators, and in particular leaders of streamlining / harmonization initiatives, concerning how their current intra-provincial processes for streamlined review could be extended to accommodate extra-provincial reviews. It could be that the first step in a national harmonization process may be “one review per Province” in accordance with the provincially adopted harmonization processes.

We also recommend that the basis for determining whether a review should be a single REB review (as opposed to review by a single REB) should be carefully considered and implemented in an incremental fashion. The limitation of the requirement to “minimal risk” reviews is arbitrary and would be challenging to implement in practice. It could be that certain types of research (eg. survey research conducted at academic institutions, research requiring limited involvement of multiple sites, research involving multiple researchers at one site) could easily lend themselves to reciprocal review or REB Authorization agreements like those utilized in the US.

In the context of the environmental scan and consultation, consideration could also be given to the concept of exemption of certain very low risk unfunded research from review, giving due consideration to the American exemption process, including their definition of “benign” research.

We would like to thank the Panel for taking the initiative to start a national dialogue on streamlining multi-site ethical reviews. As noted, we wholeheartedly support the departure from multiple single site reviews of multi-jurisdictional studies and moving toward a model encouraging a single comprehensive review. We hope that the Panel finds our comments helpful and trust that it will give due consideration to our concerns, particularly those pertaining to single REB review by a single REB.

If we can lend any assistance or advice to the Panel as it considers a way forward to achievement of the goal of harmonizing ethical review of multijurisdictional research, we would be happy to be consulted.

Thank you again for the opportunity to comment.

Research Ethics BC and UBC’s Affiliated REBs, with the exception of BC Cancer REB.

- Date modified: